December 10, 2019 | By Hannah Brauer (she/her/hers), Photographer/Writer Student Lead

For many people, the holidays are a great time of celebration. Huge pine trees with lights and ornaments, Santa meeting children at nearly every mall, reindeer-printed wrapping paper… or, that is, for those who celebrate Christmas.

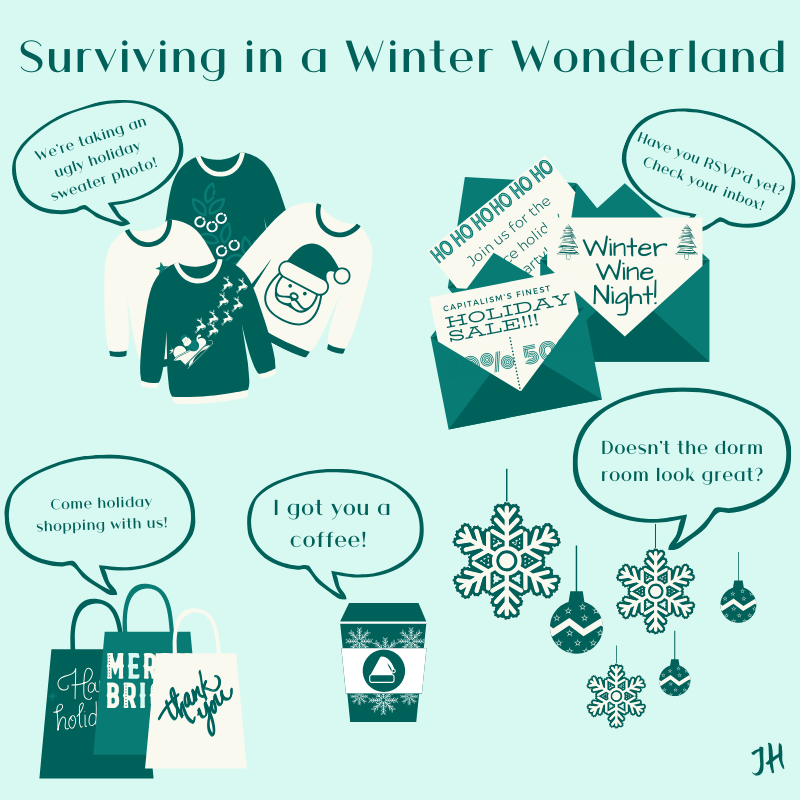

The United States is undoubtedly a Christian-centric nation — Christmas is recognized as a federal holiday, after all, and it seems the entire country’s advertising campaigns are marketed towards those buying gifts for the months of November and December. Capitalism perpetuates the presence of Christmas symbols constantly in public spaces, either through commercials or in store windows.

For those who celebrate Christmas, this bombardment may not seem anything out of the ordinary and even pull upon positive emotions associated with the holiday. For others, however, being immersed in Christmas culture can be taxing, especially if their own holidays are celebrated during this time but are overshadowed or underrepresented in public spaces, such as Hanukkah or Kwanzaa.

Oftentimes, we hear the break between December and January being called “Christmas break,” but sometimes it’s “winter break.” A similar dispute exists between saying “Happy Holidays” and “Merry Christmas” as a seasonal greeting. These disputes have touched U-M as well — the Michigan Daily featured pieces about which seasonal greeting to use and working in Christmas-centric spaces as a Jewish student.

According to Michigan Hillel, about 14% of the U-M student body identifies as Jewish, and a 2016 diversity report states representation of Hindu, Muslim, Buddhist, and other students who represent non-Christian religions. Thus, there are many students at the University of Michigan (U-M) who don’t celebrate Christmas and may be placed in difficult situations when invited to a Christmas sweater party, are asked to participate in Secret Santa for a student organization, or simply exist in public spaces decorated for the Christian holiday.

This season, think critically about which spaces are decorated for a holiday and how you can open conversations about the topic. Are you installing a Christmas tree in the office and playing Christmas music every day without thinking twice? Ask yourself the following questions when deciding whether to put up decorations or when you notice symbols in other spaces:

-

Are these symbols or decorations in a public or private space? If they are in a public area, how much space do they take up? Are they enough to ignore if needed, or are they distracting to others?

-

What is the motivation behind displaying these symbols? Is it from a genuine desire to celebrate or the urge to consume?

-

What kind of symbols are these? Are they related to Christmas specifically (i.e. Santa, reindeer, ornaments, etc.) or generally related to winter (snowflakes, mittens, sledding)?

-

Are events with members from your school, work, organization, or friend group specific to a religion? Is there a way to limit references to religion if these are mandatory or important events?

-

In schools, how can music choices during this season be approached from a non-religious perspective? Are students mostly in spaces where they must complete a Christmas-related activity, sing a Christmas song, or participate in a classroom Christmas party?

-

If you choose to display symbols from your own traditions, how can you express interest in your friends and coworkers’ traditions as well?

It’s important to think critically about our own display of decorations, especially if they play into mainstream consumerism or overshadow other religions and customs. So, when you’re shopping for wrapping paper and notice the lack of secular symbols, or see nativity scenes in front yards, open a conversation with yourself and others about how these spaces would feel to those who celebrate another holiday — or no holiday at all — during this time of year.